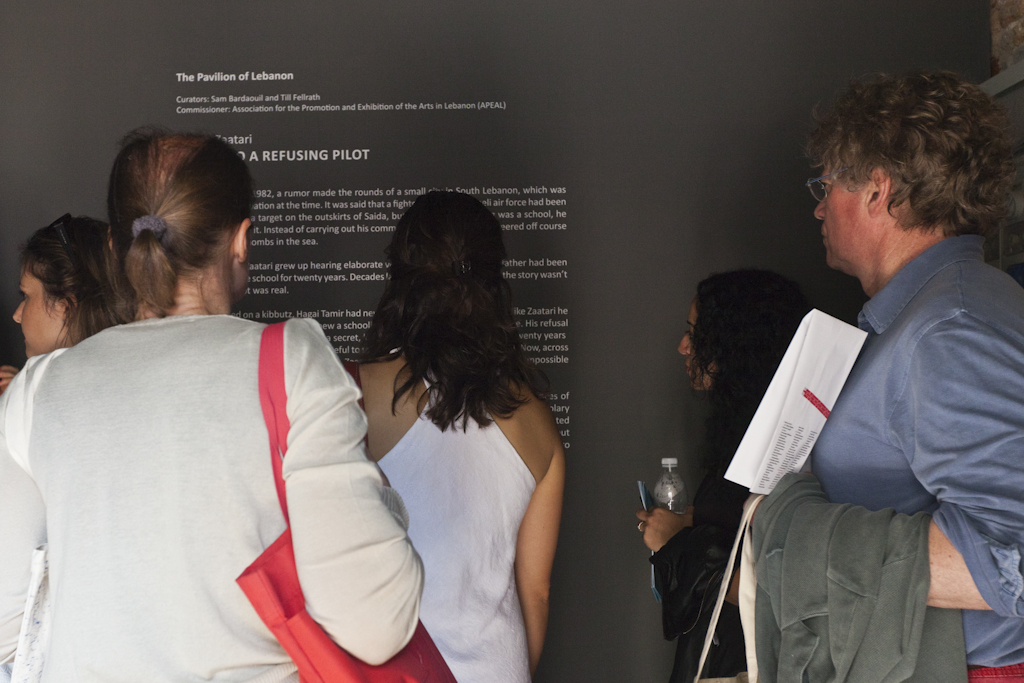

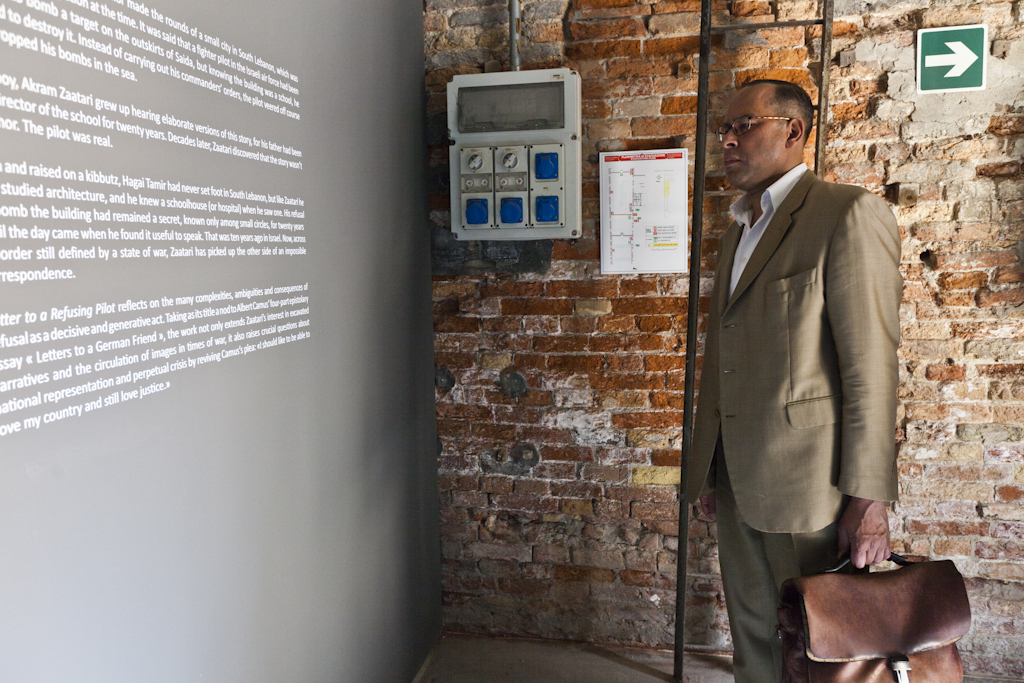

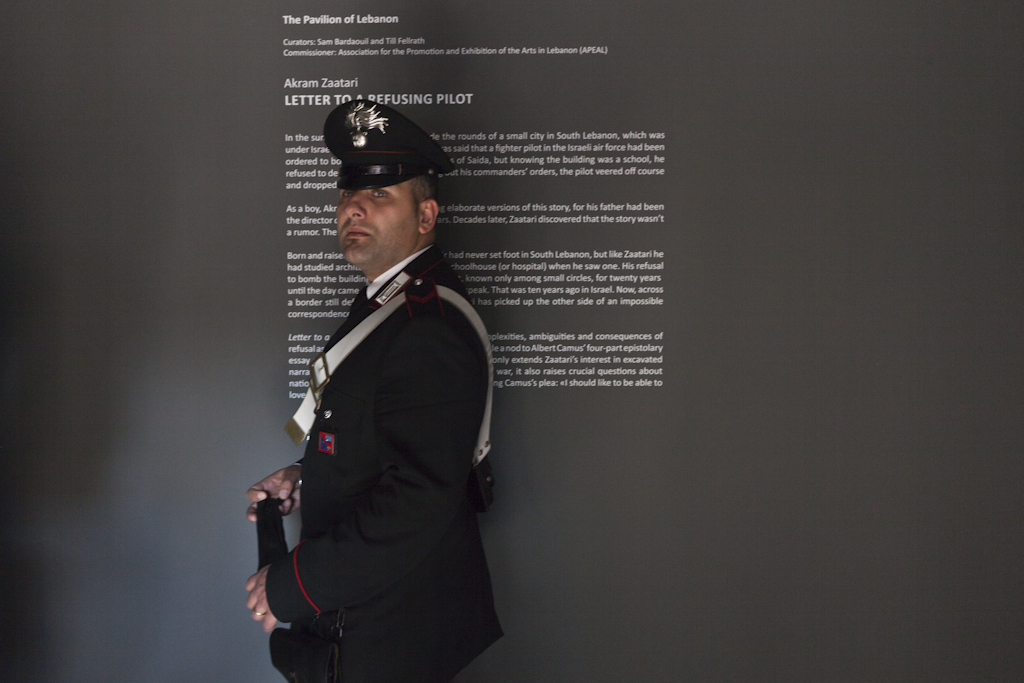

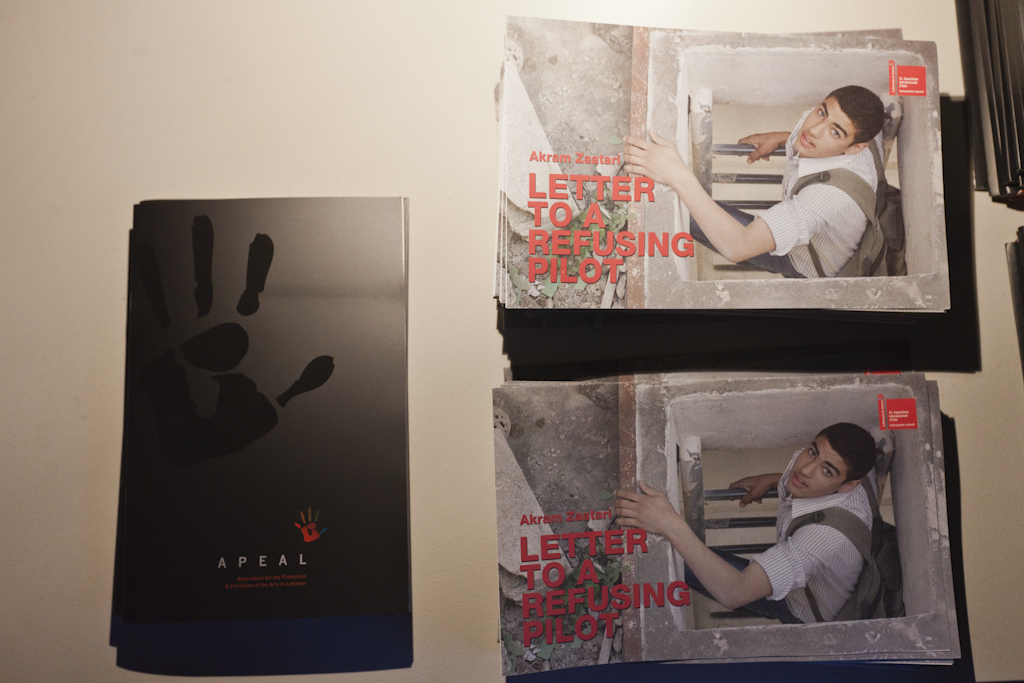

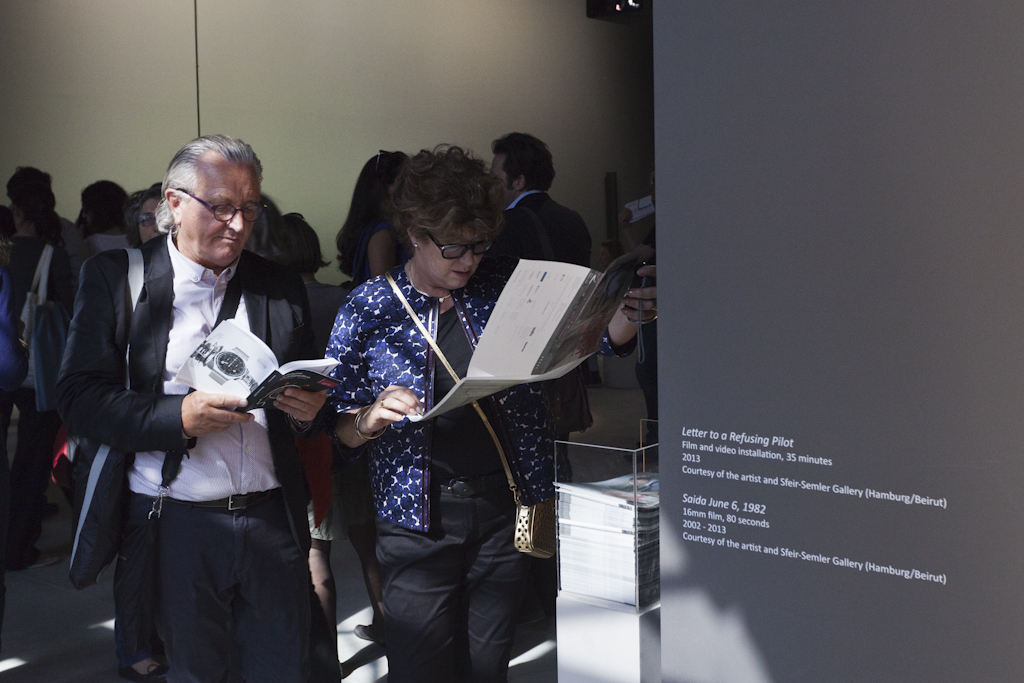

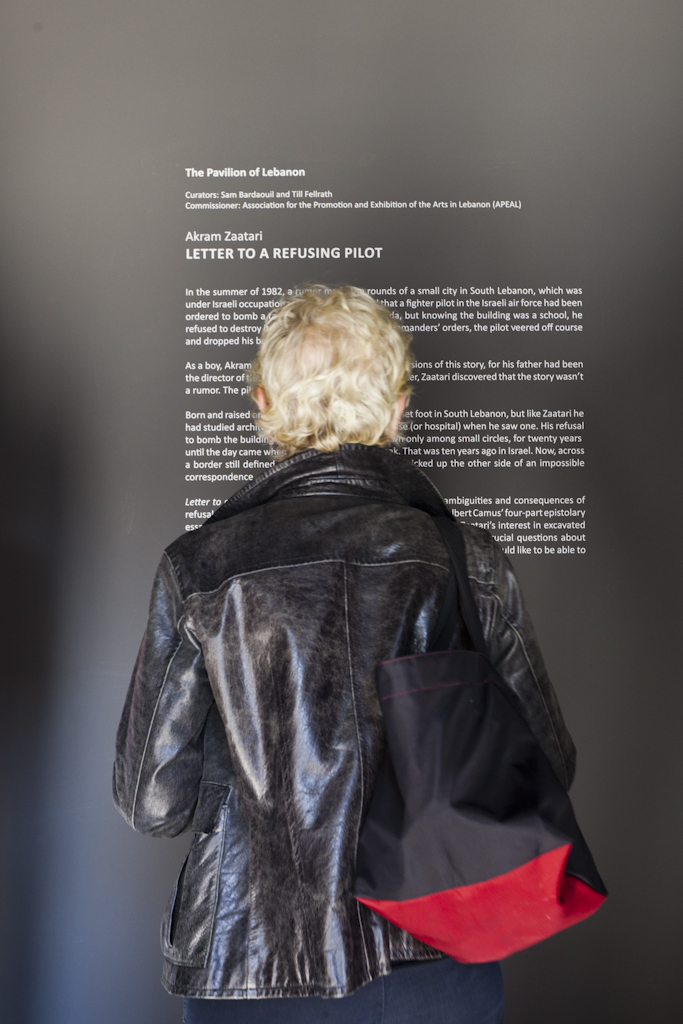

Letters to a Refusing Pilot - Akram Zaatari - Venice Biennale - 2013

In one of the opening scenes of Akram Zaatari’s film Letter to a Refusing Pilot, you see the artist’s hands turning the pages of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s novella The Little Prince.

First the cover, then the inside title, until you get to the dedication page: “À Léon Werth quand il était petit garçon,” the dedication reads.

The page that the artist chooses to show you last is one that tells of an early exchange between the narrator and the character of the little prince.

“Draw me a sheep,” says the little prince to the narrator. The narrator makes a drawing of a sheep. “No. This sheep is already very sickly. Make me another.” So he makes another drawing. The little prince smiles gently and indulgently and says: “This is not a sheep. This is a ram. It has horns.” After several rejections, the narrator’s patience is exhausted and so he draws a box and said: “This is only his box. The sheep you asked for is inside.” The little prince’s face lights up and he replies: “This is exactly the way I wanted it!”

Why would Akram Zaatari, you might ask, dedicate a significant portion of the opening sequence of his film to an ostensibly irrelevant display of a few select pages from a children’s storybook? The question is even more pertinent since the film tackles an incident that occurred during the 1982 Israeli Invasion of Lebanon where an Israeli fighter pilot refused to carry out his commanders’ orders to destroy a public school in Saida and dropped his bombs in the sea.

Here’s one attempt at an answer. Saint-Exupéry, besides being a writer and poet was a pioneering aviator. He wrote The Little Prince in 1943 while in the United States. He had left for New York in 1940 upon his demobilization from the French Air Force following France’s defeat and its armistice with Nazi Germany. But in the spring of 1943, he departed with an American convoy to fly with the Free French Air Force and fight with the Allies. In July 1944, while on a reconnaissance mission, his plane disappeared over the Mediterranean and he never returned. Léon Werth, to whom SaintExupéry had dedicated The Little Prince would eventually write at the end of the Second World War: “Peace without Tonio (Saint-Exupéry) isn’t entirely peace.”

Besides the possible correlations that you could draw between the universe of Saint-Exupéry and The Little Prince, and the story of refusal picked up by the artist, you are not left with many more clues as to why Akram Zaatari has chosen to open his film with a vivid mention of this children’s fable. There will be many other unresolved and open-ended questions that the artist wants you to encounter in this work. But you won’t mind. For soon you will find yourself taken by another tale, one that is far more sober. Soon, you will learn that this is Akram’s personal story and its culmination around June 6, 1982.

In the summer of that year, a rumor made the rounds of a small city in South Lebanon, which was under Israeli occupation at the time. It was said that a fighter pilot in the Israeli air force had been ordered to bomb a target on the outskirts of Saida, but knowing the building was a school, he refused to destroy it. As a boy, Akram Zaatari grew up hearing ever more elaborate versions of this story, for his father had been the director of that very school for twenty years.

In his Letter to a Refusing Pilot, Akram Zaatari immerses you in a non-linear narrative that blurs the boundaries between an elusive past and the tangible present. At times, he presents you with rare pictures from the late 1950s and 1960s of the Taameer district in which the school resides. Some of these are by François Ecochard, the main architect who designed the project. He then briskly transports you into scenes of that same school and neighborhood taken from new footage that he recently shot for the film. Specific vantage points from which certain buildings and sites were recorded in the past are re-enacted revealing the tear and wear of time, and how the experience of war and an overload of inhabitants could transform, almost beyond recognition, what once was a visionary architectural feat. As scene after scene unravel, you understand that the film acts as homage to architecture – Akram Zaatari studied architecture - and how the destruction of one building impacts the life of an entire city and the manner in which its inhabitants use it.

Alongside the temporal fluidity that permeates across the film, Akram Zaatari masterfully weaves five decades’ worth of archival materials into photos from family albums and images he made in his youth. He complicates the otherwise obvious distinction between the personal object and the public record. At a certain moment, for instance, he juxtaposes a page from his brother Ahmad’s diary with a document that constitutes an official record of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. You soon notice that both, the entry in his brother’s diary and the page selected from the public archive show a similar Israeli fighter jet hovering over the skies of Lebanon. The conflation of the personal with the public, not unlike several other works by Akram Zaatari, makes you question the context in which personal biographies exist, including your own. To what extent are your choices, ones that you deem triggered by personal circumstance and conviction, truly autonomous from the canonical histories and lawful attitudes that are decreed by our nations?

In his publication A Conversation with an Imagined Israeli Filmmaker Named Avi Mograbi, Akram Zaatari writes:

“We have learned that facts have at least two faces.

Maybe a conversation between two documentary filmmakers about banalities would never have been an issue. Its importance lies in the fact that we come from two enemy states. Our presumed conversation is based on an irresolvable conflict and a history of occupation between two nations, both founded on what remained of the Ottoman Empire, with borders drawn by the French and the British, and declared as independent states with precise borders and flags by the UN. Lebanon, 1943. Israel, 1948.

In Notre Musique, Godard reads while commenting on two photographs, which are only superficially similar:

‘In 1948, the Israelites walked in the water towards the Promised Land. The Palestinians walked in the water to drown. Shot and reverse shot. The Jewish people join fiction. The Palestinian people, the documentary.’

Which fiction and what documentary?

Aren’t nations like fictions? Aren’t borders like fictions established on a continuous landscape, across continuing cultures, while we are led to believe that the states we live in are finalities, a natural culmination of an organic evolution?”

Now, in Letter to a Refusing Pilot, Akram Zaatari builds on the tropes of interrogation that he established in his Conversation in order to further question how nations are articulated vis-à-vis their position towards other states. This he does by confronting individual ethics with collective lawful duty. As the film progresses, you find yourself asking the ever-critical question of how could one follow what one believes to be morally right when it contradicts the jurisdiction of state law. That this act of interrogation is taking place within the confines of a pavilion whose entire rasion d’être lies within the notion of national representation is undoubtedly ironic. However, it is for that reason that both, the work and the platform through which it is presented, acquire a more potent agency.

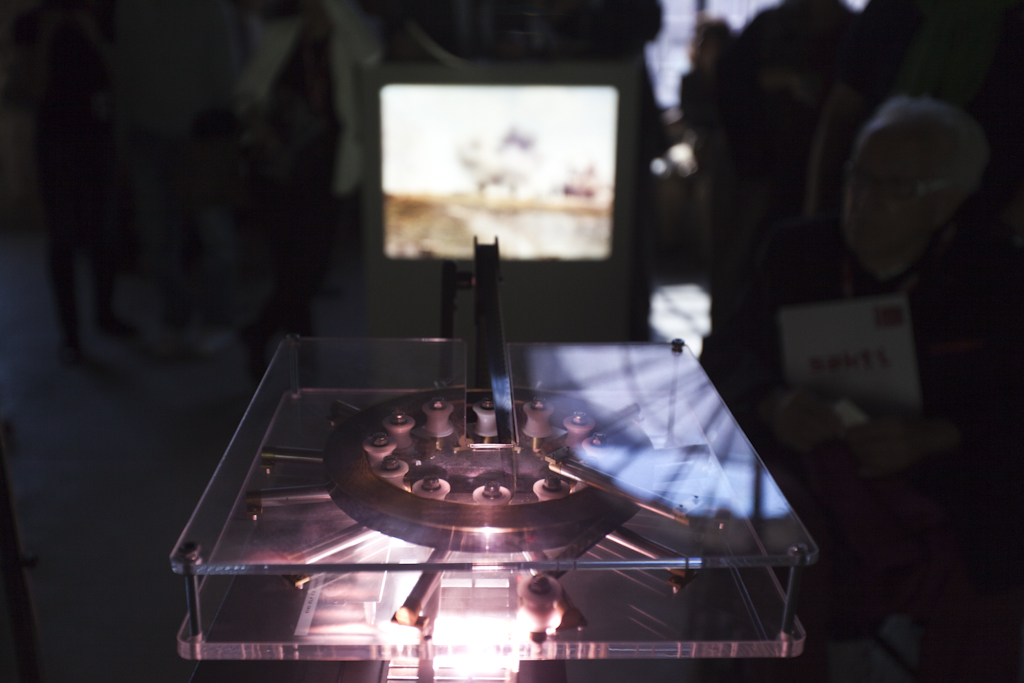

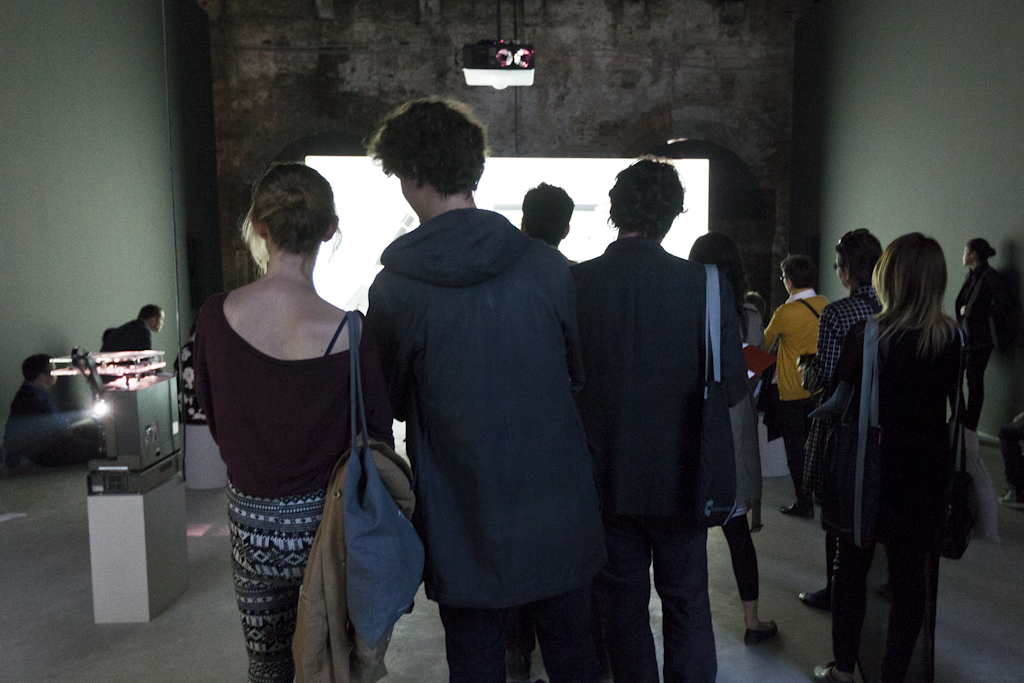

And then there is that vintage theatre seat with its striking velvety-red color sitting in the heart of the entire installation. An intimate viewing space meant for you alone not to be shared with other people. A time capsule whereby you are transported not only to that very distinct chapter in Akram Zaatari’s life, but also to a traumatic episode in the life of an entire nation. In a Brechtian twist, you find yourself at once becoming the spectator, the narrator and a wide array of characters all embroiled in this Epic Theatre where the fourth wall, the suspension of disbelief are at once nurtured and destroyed. You find yourself at the heart of a dialogue between two works, a new 45-minute video and a looping 16mm film, within an environment conceived as a stage awaiting an actor, or a cinema awaiting a spectator. It only takes a little while before you recognize how Letter to a Refusing Pilot, despite its rootedness in a very specific and personal story, touches upon a human characteristic deeply-seated in us all: the ability to dream up a world that exists beyond the reality of the one we live in. One where nations can exist outside the delineations of borders and geographies, where histories can be unmade and injustices reversed; where your personal choices are not conflicting with the jurisdictions of state law and if so, can go un-punishable.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s little prince embodies the spirit of wonder that comes from the ability to see the world through the eyes of a child, and in doing so, inhabits a universe that does not function by the rationality of adults and the systems they create to govern their existence. The prince could see the little sheep he desired even though it was hidden inside the box. In his Conversation, Akram Zaatari tells us that as a teenager during the months following the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, he photographed destroyed buildings, Israeli vehicles and damaged cityscapes, but could never take pictures of soldiers. As a matter of fact, he avoided eye contact with soldiers. Today, Letter to a Refusing Pilot, may well be Akram Zaatari’s way of looking those soldiers, one in particular, in the eye; of seeing through the locked box and exploring, like the little prince the infinite possibilities of a new conversation that ironically has its origins in a decisive act of refusal.

In the dedication page that you see towards the opening of the film, you get a glimpse of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s words to his friend:

“To Léon Werth I ask the forgiveness of the children who may read this book for dedicating it to a grown-up. I have a serious reason: he is the best friend I have in the world. I have another reason: this grown-up understands everything, even books about children. I have a third reason: he lives in France where he is hungry and cold. He needs cheering up. If all these reasons are not enough, I will dedicate the book to the child from whom this grown-up grew. All grown-ups were once children − although few of them remember it. And so I correct my dedication:

To Léon Werth When he was a little boy”

Children write the sweetest letters, and the wisest ones too.

Gallery